Abstract

Introduction:

Although tuberculosis has been a very common disease in endemic areas, isolated involvement of the breast was uncommon. The coexistences of breast carcinoma and tuberculosis mastitis was very rare but could create a dilemma in the diagnosis and treatment, as there were usually no pathognomonic features to differentiate malignancy from breast tuberculosis.Case Presentation:

We have reported the case of a 40-year-old woman referred with a painful lump in her left breast and nipple retraction. Mammography has shown an irregular mass and pleomorphic micro calcifications. Breast ultrasound has revealed a hypo echoic irregular mass. The first diagnosis was breast carcinoma. Histological study confirms high grade ductal carcinoma in situ. There was also evidence of tuberculosis mastitis at histological examination of the breast specimen.Conclusion:

Breast tuberculosis has known as a rare disease even in endemic countries. Coexistence of breast carcinoma and tuberculosis mastitis is very rare but it could lead to many problems regarding diagnosis and treatment.Keywords

Breast Breast Cancer Breast Tuberculosis Mastitis Tuberculosis

1. Introduction

Nearly 18% of tuberculosis cases have shown only extra pulmonary manifestation (1). Breast tuberculosis has been a rare type of extra pulmonary tuberculosis (2). The significance of breast tuberculosis was due to mistaken identify with breast cancer and pyogenic abscess (3). Breast tuberculosis has been rare in the western countries but, with the global spread of AIDS, tuberculosis mastitis might be no more common in the developed world. The prevalence has estimated to be 0.1% of breast lesions examined histologically (3, 4), and it has constituted about 3% - 4.5% of surgically treated breast disease in developing countries (3). The first case of breast tuberculosis has reported by Sir Astley Cooper in 1829 who called it ((Scrofulous swelling of the bosom)) (5). Breast tuberculosis had no defined clinical manifestation that could confuse the clinician by its resemblance to carcinoma or non- specific abscess (3, 6).

Imaging modality like mammography or ultrasonography was of limited value as the findings are often nonspecific and in distinguishable from malignancy or chronic breast abscess (4-6).

Early diagnosis was difficult. It has warranted a high index of suspicion on clinical examination and pathologic or microbiologic confirmation of all suspected breast lesions. Breast carcinoma and tuberculosis mastitis might rarely coexist but, there were usually no pathognomonic symptoms or signed to distinguish both disease (4-6).

The main purpose of this article was to remained clinicians, radiologist and pathologists of such condition. We would present a 40-year old woman with simultaneous involvement of tuberculosis mastitis and breast carcinoma.

A brief review of literature has also done, to illustrate the clinical and radiological presentation and also, to evaluate the diagnosis challenges.

2. Case Presentation

A 40-year-old lactating woman has referred to the breast clinic with a painful lump in the left breast which has been present for 10 months. There was no evidence of nipple discharge and she complained of no other symptoms. Her past medical history was unremarkable and there was a family history of breast cancer .Her mother had died of breast cancer about 15 years ago.

Clinical breast examination has revealed a firm, semi- fixed 2 × 3 cm mass at the central region of her left breast associated with nipple retraction, mild skin thickening and erythema (Figure 1).

A 40-Year-Old Woman with a Breast Lump, Nipple Retraction and Skin Erythema in Her Breast

There was no evidence of axillary lymphadenopathy and examination of the right breast was normal.

General physical examination was otherwise normal.

The patient has referred for mammography (Figure 2) which has shown an irregular mass measuring 2 × 2 cm at the central region of the breast. Also, mammography has revealed multiple pleomorphic micro calcifications at the central part and upper outer quadrant of the breast suggesting malignant micro calcifications (Figure 3). There was also asymmetric increased parenchyma density in the retro areolar region associated with nipple retraction.

Mammogram of the Left Breast in craniocaudal View Shows an Irregular, Speculated Mass Lesion in the Central Region of the Breast (Black Arrow) Associated with Multiple Pleomorphic Macro Calcification (White Arrow)

Focal Compression Magnification View of the Left Breast Demonstrates Multiple Foci of Pleomorphic Micro Calcifications

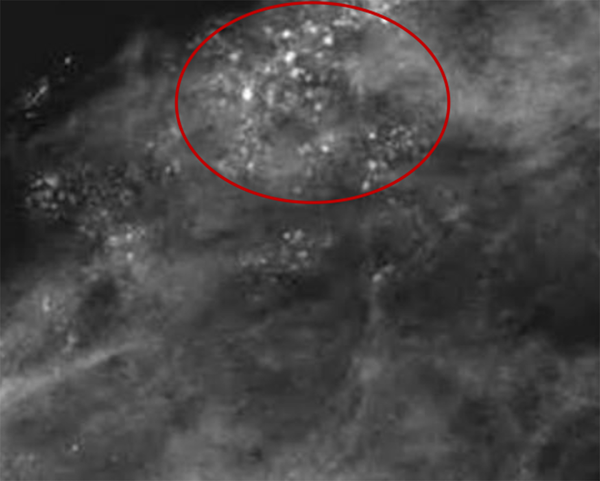

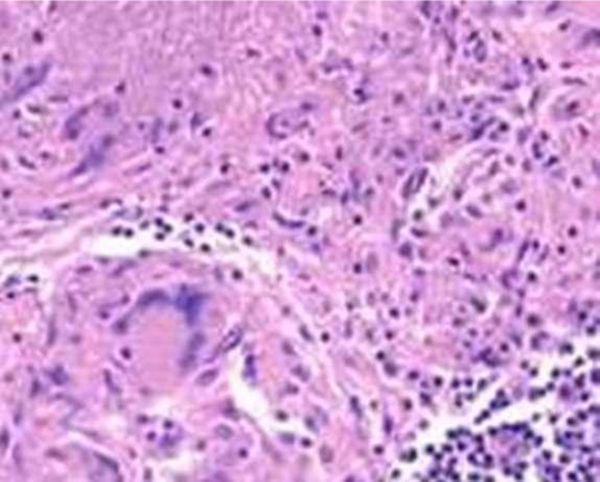

Ultrasound of the left breast has shown a hypo echoic and irregular mass at the central region of the left breast with heterogeneous internal echo and without distal shadowing, measuring 21 × 24 × 30 mm (Figure 4). The provisional diagnosis of breast cancer has suggested and the patient has admitted for excisional biopsy. Histological study of the specimen has demonstrated granulomatous lesion with caseation granuloma containing multinucleated langhans, giant cells, epitheliod histiocytes, (Figure 5) along with evidence of high grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS ) with invasive component (Figure 6). Special ziehl-Nelson, s staining revealed acid-fast bacilli within macrophages, confirming tuberculosis mastitis.

Ultrasound Image of the left Breast Shows a Hypo Echoic Mass Lesion with Irregular Margins and Heterogeneous Internal Echoes (Arrow)

Histological Examination Revealed Granulomatous Lesion with Caseation Granuloma and the Presence of Giant Cells and Epithelial Histiocytes (Haematoxyline and Cosin Stain; original Magnification × 400)

Histological Examination Revealed High-Grade Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) Neoplastic Cells Have Clumped Chromatin, Some with Multiple Nucleoli

Lymph node sampling has shown no metastatic involvement of axillary lymph nodes and there was also no evidence of granulomatous lesion in the axillary lymph nodes. Chest x-ray was normal and there was no evidence of abdominal metastasis in the liver and Para aortic lymph nodes.

Routine laboratory examinations were normal except erythrocyte sedimentation rate which was 32 mm/h.

The patient has undergone a left simple mastectomy. The patient had an uncomplicated course. After the final diagnosis of the breast tuberculosis, she has undergone a complete work up including chest X-ray, abdominal computed tomography, to rule out other foci of tuberculosis. After mastectomy the patient has received anti-tuberculosis drugs with daily doses of 300 mg isoniazid, 600 mg rifampin, 1500 mg pyrazinamide, and 10 mg pyridoxine for six months without any side effects. The patient has regularly followed for another 12 months and no evidence of recurrence of her disease has noted. An informed consent was taken from the Patient.

3. Discussion

The incidence of tuberculosis has been rising worldwide and rare manifestation of the past has seen more often now a day. Tuberculosis of the breast was uncommon in developed countries (7, 8).

It has been rare even in countries where tuberculosis is still common, accounting for only 0/1% of all breast lesions (3, 7).

This was probably due to increased mammary gland tissue resistance to the survival and multiplication of mycobacterium tuberculosis, under diagnosis of tuberculosis mastitis and anti-tubercular treatment (7). There would be a hypothesis that breast tissue, like skeletal muscle and spleen has been resistant to mycobacterium bacilli (8). It has believed that immigration from endemic areas and increased number of immune compromised patients particularly after the human immune deficiency virus episodes might be responsible for over estimating the incidence of tuberculosis mastitis in western countries in the future (7, 8).

Mammary tuberculosis might be primary or secondary, and the breast might be infected in various ways eg, (i) haematogrneous, (ii) lymphatics, (iii) spread from contagious structures, (iv) direct inoculation, and (v) ductal infection (3, 8). It has believed that breast infection has usually been secondary to a pre-existing tuberculosis focus, somewhere else in the body such as the lungs or lymph nodes. Primary breast tuberculosis has been quite rare and the disease might diagnose as a primary lesion because the clinician was unable to detect the true focus of the disease. In these cases, coincidental tuberculosis of the facial tonsils of suckling infants has suggested as one of the common routes of breast tuberculosis spreading from the suckling to the nipple, and in turn, to the lactating breast via lactiferous ducts .This might be the sole example of primary breast tuberculosis (3). Mycobacterium tuberculosis has usually penetrates in to the breast through the lactiferous duct via the nipple, a penetrating wound of the skin of the breast, direct extension from the lungs and thoracic wall, the lymphatic and the bloodstream (3, 4, 7). Breast has been resistant to tuberculosis infection by blood stream even in debilitated patients with tuberculosis .Our patient has not shown any features of tuberculosis outside the breast, both on physical and radiological examination.

Predisposing factors for tuberculosis mastitis have considered as young age, multiparty, lactation, poor general health, stress of childbearing and trauma (3, 9). A young multiparous lactating woman with a breast lesion especially in the presence of poor general health should start the suspicion of breast tuberculosis in endemic areas. Male have rarely affected (3). Bilateral involvement has been uncommon (4, 5).

The history of the presenting symptoms in the breast is usually less than a year but varies from few months to several years; Solitary breast lump would be the predominant clinical presentation of breast tuberculosis, which the commonest location of the lump is the central or upper outer quadrant of the breast. The mass could be fluctuated and has usually covered with indurated tissue. It has usually fixed to the skin and fistulization could be common (1, 7, 10). Diffuse breast nodularity, nipple and skin retraction, skin thickening and ulceration, erythema and swelling could also occur, but breast discharging and pain were not common presentation (7-9). Breast deformity and multiple sinuses might see in advanced cases (7, 8, 10). From the clinical point of view, mastalgia with masses, and discharge should drew the attention to an infective breast disease, and breast tuberculosis should be suspected if the symptoms were longstanding specially in endemic countries (1-10).

There have not appeared to be a causal link between breast tuberculosis and breast carcinoma, any there was no evidence that tuberculosis was carcinogenic at any site (4). The clinical situation that raised were the presence of cancer and tuberculosis mastitis, carcinoma in the breast with axillary tuberculosis lymphadenopathy or both (11, 12). Pandey has reported a case of invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast, metastasis to axillary lymph nodes with tuberculosis adenitis in the same lymph node (13). The coexistence of carcinoma and breast tuberculosis could lead to many problems regarding diagnosis and treatment (11). Differentiate breast cancer from tuberculosis, especially if the lesion has located at the upper outer quadrant of the breast (6-13) clinical features such as constitutional symptoms, mobile breast lumps, multiple sinuses and an intact nipple especially in young, multiparous or lactating woman have shown predictive features but not diagnostic for breast tuberculosis. An isolated breast mass without any associated sinus tract could commonly mimic the presentation of breast cancer (4-14). Clinical features such as nipple retraction, peaud, orange and axillary lymphadenopathy were more common in breast cancer than in tuberculosis mastitis (8, 14). Our patient has presented with a breast lump and nipple retraction.

Breast tuberculosis has first classified into five different types by McKeon and Wilkinson: (i) nodular tubercular mastitis, (ii) disseminated tubercular mastitis, (iii) sclerosing tubercular mastitis, (iv) tuberculosis mastitis oblitrans, and (v) acute milliary tubercular mastitis (15). Breast tuberculosis has newly classified as nodular, disseminated, and sclerosing variety (7-10)

The most frequent clinical form is nodular type that observed in the patient which described in this report. Nodular form may be mistaken for fibro adenoma or breast carcinoma, the disseminated form is the least common type and could be mistaken for inflammatory cancer, sclerosing type has occurred usually in the elderly and may cause diffuse fibrosis, nipple retraction and breast deformity, being mistaken for schirrosis cancer (7-10).

Imaging modalities, like mammography or ultrasound (US) have shown limited value in the diagnosis of breast tuberculosis as the findings were often indistinguishable from breast cancer. The modern imaging investigations such as computed tomography (CT-scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast, have helped for defining the extent of the lesion rather than in diagnosis (1-13). The chest X-ray might show evidence of active or healed tuberculosis lesion in the lungs in a few cases and might also reveal clustered calcifications in the axillary region suggesting the possibility of lymph nodes tuberculosis in suspected patient. The mammogram in breast tuberculosis was of limited value as the findings are often indistinguishable from breast carcinoma. Also, as breast tuberculosis has found in young women of 20 - 40 year of age, dense breast has caused interpretation of mammogram difficult.

Mammography might show breast mass usually with an ill-defined borders, coarse stromal texture, and focal or diffuse asymmetric breast density, focal or diffuse skin thickening and nipple retraction (6). In nodular form mammography might demonstrate a mass with regular margins or irregular borders due to abscess formation with peripheral edema or scaring tissue mimicking breast cancer. In diffuse form there were usually multiple inter communicating foci of tuberculosis associated with edema and inflammatory reaction mimicking malignancy.

In the sclerosing form fibrosis was a dominant feature, which accounted for two mammographic features. The first was the reduction and retraction of the breast tissue, which was secondary to fibrotic process. The second effect was the asymmetry in breast tissues, as once fibrosis ensues the breast became dense. In malignancy, breast atrophy and deformity was not a remarkable sign. Multifocality and multicentricity of the lesions associated with multiple skin lesions favors tuberculosis mastitis rather than breast carcinoma (1-10). Calcification in breast tuberculosis was rare and the calcifications were usually large, round and non-clustered (7, 8).

Mammographic demonstration of a dense sinus tract has been connecting an ill- defined breast mass to a localized skin thickening and bulge (skin bulge and sinus tract sign) was strongly suggestive of tuberculosis mastitis (6). This sign has reported by makanjuola. However khanna has reported this sign in only 1 out of 7 patients who had mammogram done in his series of 52 patients, emphasizing the rarity of this sign (5). The mammographic size of the tuberculosis lesion correlates well with its clinical size, unlike that of a carcinoma.

Ultrasound (us) has known as an essential complementary modality to mammography. In nodular form of the disease, US has usually shown a heterogeneous fluid containing mass with or without internal septation mimicking a complicated cyst, breast abscess or a necrotic tumor .In diffuse form of breast tuberculosis ill -defined hypo echoic masses have seen whereas in patients with sclerosing type, increased echogenecity of the parenchyma often with no definite mass has seen.

In many patients, the fibrosis and interlobular edema might mask the breast mass at mammography. Here US could identify breast masses masked by the dense breast tissue (1-13). The nodular form of breast tuberculosis might mimic fibro adenoma with a regular contour, hypo echoic pattern, and posterior enhancement (7-10). Axillary lymph adenopathy would be a common finding in chronic tuberculosis mastitis. US was a sensitive technique to detect the axillary lymph nodes, and might help to suggest the benign rupture of their enlargement by the presence of echogenic hillar fat and preservation of oval shape (13). Our patient had mammographical features typical of malignancy, and US findings were also nonspecific for tuberculosis abscess.

CT scan seldom has added to the diagnostic yield other than in defining the involvement of thoracic wall in patients presenting with deeply adhered breast lump. CT scan would be a valuable tool in demonstrating the extent of disease, in planning surgery and also in assessment of response to treatment.

MRI of the breast might reveal a smooth or irregular bright signal at T2-wighted images suggesting breast abscess .MRI findings were nonspecific and only useful in demonstrating the extra mammary extent of the lesion

Diagnosis of the disease has required cytological evidence of epithelial granulomas, Langhance giant cells, and lymphohistiocytic aggregates, for a confirmed histological diagnosis .The most common finding of histological examination was evidence of epitheloid cell granulomas. Core needle biopsy with a good sample often yielding a positive diagnosis .However open biopsy (incision or excision) of breast lump, ulcer, sinuse or from the wall of a suspected tubercular abscess cavity has almost always confirmed the diagnosis. The frequency of a positive stain for acid- fast bacilli (AFB) in the specimen has reported to be lower and not essential for confirming the diagnosis. None of the patients who have been reported by kalac or khanna had positive staining for AFB (2-5). AFB-negative breast abscess that fail to heal despite adequate drainage and antibiotic therapy, and those with persistent discharging sinuses should raise the suspicions of underlying tuberculosis.

Fine needle aspiration and cytology (FNAC) from the breast lesion has continued to remain an important diagnostic tool of breast tuberculosis and could establish the diagnosis in most cases. Khanna has reported a success rate of 100% in his series (5). Approximately 73% to 100% of cases of breast tuberculosis could be diagnosed on FNAC when both granulomas and necrosis have been present (3, 8).

Gene amplification methods such as Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has developed for the diagnosis of tuberculosis, were highly sensitive especially in culture-negative specimens from paucibacillary forms of disease. PCR in the diagnosis of breast tuberculosis has less often reported, mostly as a tool to distinguish tubercular mastitis from other forms of granulomatous mastitis in selected cases. However, PCR was by no means absolute in diagnosing tubercular infection and false positive results were still a possibility.

Most decision in the management of breast cancer has taken based on TNM system. In patients with coexistence of breast tuberculosis and cancer this could lead to overestimation of the tumor size, therefore these patients lose the opportunity for breast conservation due to this. The form of breast surgery was dependent upon the stage of breast cancer (11-16). In patients with clinically operable lesion, radical mastectomy has indicated, followed by anti-tubercular treatment (ATT) for 6 - 12 months, and if breast cancer was not curable, palliative therapy combined with ATT have indicated (12, 13). The drug regimen has generally followed during the treatment of breast tuberculosis was similar to that used for pulmonary tuberculosis, and consisted of the combination of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin and pyrazinamide (1-10). Anti-tubercular therapy with four drugs is the primary line of treatment of tuberculosis. The six-month treatment regimen has comprised two months of intensive phase (include four medicines: ethambutol, pyrazinamide, rifampicin, isoniazid) followed by four months of continuation phase (with two drugs: isoniazid and rifampicin).

In breast tuberculosis without concomitant breast cancer minimal surgical intervention has required for drainage of breast abscess or biopsy from the abscess wall and scraping of sinuses in the breast .Simple mastectomy with or without axillary clearance has rarely used for extensive disease comprising large, ulcerated breast lesion involving the entire breast and axillary lymph nodes rendering organ preservation impossible (16).

3.1. Conclusions

Breast tuberculosis has known as a rare disease even in endemic countries. Coexistence of breast carcinoma and tuberculosis mastitis is very rare but it could lead to many problems regarding diagnosis and treatment. Clinical features and imaging findings often fails to distinguish breast cancer from tuberculosis mastitis and histological examination would be essential for correct diagnosis and an appropriate management of the patient.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

Mirsaeidi SM, Masjedi MR, Mansouri SD, Velayati AA. Tuberculosis of the breast: report of 4 clinical cases and literature review. WHO; 2007.

-

2.

Kalac N, Ozkan B, Bayiz H, Dursun AB, Demirag F. Breast tuberculosis. Breast. 2002;11(4):346-9. [PubMed ID: 14965693]. https://doi.org/10.1054/brst.2002.0420.

-

3.

Madhusudhan KS, Gamanagatti S. Primary breast tuberculosis masquerading as carcinoma. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(1):e3-5.

-

4.

Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, Mazahreh TS. Tuberculous mastitis: a disease not to be forgotten. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 2005;9(8):920-5.

-

5.

Khanna R, Prasanna GV, Gupta P, Kumar M, Khanna S, Khanna AK. Mammary tuberculosis: report on 52 cases. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(921):422-4. [PubMed ID: 12151660].

-

6.

Makanjuola D, Murshid K, Al Sulaimani S, Al Saleh M. Mammographic features of breast tuberculosis: the skin bulge and sinus tract sign. Clin Radiol. 1996;51(5):354-8. [PubMed ID: 8641100].

-

7.

Fadaei-Araghi M, Geranpayeh L, Irani S, Matloob R, Kuraki S. Breast tuberculosis: report of eight cases. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11(4):463-5.

-

8.

Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: diagnosis, clinical features & management. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122(2):103.

-

9.

Shinde SR, Chandawarkar RY, Deshmukh SP. Tuberculosis of the breast masquerading as carcinoma: a study of 100 patients. World J Surg. 1995;19(3):379-81. [PubMed ID: 7638992].

-

10.

Jalali U, Rassl S, Khan A. Tuberculose mastitis. J Cell Phys. 2005;5:234-7.

-

11.

Tulasi NR, Raju PC, Damodaran V, Radhika TS. A spectrum of coexistent tuberculosis and carcinoma in the breast and axillary lymph nodes: report of five cases. Breast. 2006;15(3):437-9. [PubMed ID: 16198111]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.008.

-

12.

Alzaraa A, Dalal N. Coexistence of carcinoma and tuberculosis in one breast. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:29. [PubMed ID: 18318914]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-6-29.

-

13.

Pandey M, Abraham EK, K C, Rajan B. Tuberculosis and metastatic carcinoma in axillary lymph node: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2003;1(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-1-3.

-

14.

Akcay MN, Saglam L, Polat P, Erdogan F, Albayrak Y, Povoski SP. Mammary tuberculosis–importance of recognition and differentiation from that of a breast malignancy: report of three cases and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5(1):67.

-

15.

Mc KK, Wilkinson KW. Tuberculous disease of the breast. Br J Surg. 1952;39(157):420. [PubMed ID: 14925323].

-

16.

Miller RE, Salomon PF, West JP. The coexistence of carcinoma and tuberculosis of the breast and axillary lymph nodes. Am J Surg. 1971;121(3):338-40. [PubMed ID: 5546335].