Abstract

Background:

Aspiration is one of the important complications of general anesthesia, although infrequent as well as accompanying high morbidity and mortality. The volume of gastric content is considered as a risk factor in this regard. Therefore, it is normally mostly recommend to consider proper fasting time before induction of general anesthesia.Objectives:

This study was conducted to assess the effect of metoclopramide on reducing gastric contents in patients with incomplete fasting before induction of general anesthesia.Methods:

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on patients with urgent surgical indications with incomplete NPO time. Every other patient received metoclopramide or placebo. Patients in the intervention group received 10 mg (2 ml) of intravenous metoclopramide, and patients in the control group received 2 ml of distilled water as a placebo. Patients in both groups underwent ultrasonography before starting surgery by an expert radiologist to calculate gastric antral grade (GAG) and cross-sectional antral area (CSA). These measurements were then taken for the second time 30 minutes after intervention, before starting the surgery. The values were compared statistically.Results:

The data of 60 patients were analyzed, of which 30 were in each group. The mean age, body mass index, type of the last consumed food (solid or fluid), NPO time in the two groups were not significantly different (P value > 0.05). The number of patients in the metoclopramide group with higher GAG (P value = 0.001) and the mean CSA (P value = 0.004) before the intervention was more than the control group. The GAG and mean CSA after intervention were not significantly different between the two groups; but the mean difference of decrease in CSA in the metoclopramide group was more than the control group (4.3 vs. 0.99; P value = 0.001), and changes of GAG after intervention to lower levels in the metoclopramide group was more than the control group (P value < 0.05).Conclusions:

In the current study in which ultrasonographic indexes, including GAG and CSA, were assessed as a suboptimal gastric emptying test method, it was found that metoclopramide could accelerate gastric emptying compared to placebo in patients with incomplete fasting before induction of general anesthesia.Keywords

Gastric Emptying Gastrointestinal Contents Metoclopramide Respiratory Aspiration Ultrasound

1. Background

Aspiration is one of the important complications of general anesthesia, although infrequent as well as accompanying high morbidity and mortality (1). The volume of gastric content is considered as a risk factor in this regard. Therefore, it is normally mostly recommend to consider proper fasting time before induction of general anesthesia (2-5). Proper fasting is possible before elective surgeries, but in emergencies, conditions are naturally different. Therefore, researchers are working to reduce the risk of aspirations in such situations. Recently, gastric ultrasound has been frequently used to estimate the gastric volume before the induction of general anesthesia as a valid measurement technique. This technique has made it possible to study the efficacy of different interventions to reduce the volume of gastric contents (6, 7). On the other hand, various agents have been used to accelerate gastric emptying or to increase its fluid pH, with the aim of shortening the fasting time before surgery (8-11). The management of a sub-optimally fasted patient undergoing anesthesia is a common dilemma in clinical practice. Metoclopramide has long been known as an agent that facilitates gastric emptying (12-14); despite this, there has been very little research into the effects of metoclopramide on gastric emptying prior to surgery in the recent years. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, the effect of metoclopramide in this regard has not yet been measured with ultrasound technique in preoperative settings.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to assess the effect of metoclopramide on reducing gastric contents in patients with incomplete fasting before the induction of general anesthesia.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This quasi-experimental study was conducted from 22-6-2019 until 22-10- 2019 in Imam Hosein hospital, Tehran, Iran. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1398.186). The researchers fully adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration throughout the study. Written consent after explaining the procedure has been taken from the patients. The study has been registered at www.irct.ir (IRCT20120430009593N12).

3.2. Study Population

Patients with urgent surgical indications (e.g., anal abscess, appendectomy, etc.) with insufficient NPO time (have NPO time less than eight hours for solid food and less than two hours for fluids) were eligible. Lack of sufficient time for performing the intervention and ultrasonography, known allergy to metoclopramide, inability to create the proper position for performing ultrasonography, body mass index (BMI) more than 35, gastrointestinal obstruction, prior gastric surgery, hiatal hernia, gastrointestinal reflux disease, diabetes, and those patients who were treated with stimulant drugs were excluded. The patients were also excluded if they consumed food or water, or vomited after drug administration. Based on the study of Hakak et al. (15) the least sample size was calculated as 30 patients in each arm of the trial. This study was a parallel clinical trial, with an allocation ratio of 1:1.

3.3. Intervention

We did not perform standard randomization, and every other patient received metoclopramide or placebo. But the investigator who performed the ultrasonography was blinded to the arms of the trial and was unaware of which patient received metoclopramide and which one of the placebo. The anesthesiologists were responsible for primary data gathering and eligibility assessment of the patients, while they also administered the drug in both groups. An expert radiologist was responsible for performing ultrasonography and radiological measurements. First, an electrocardiogram was performed, and any patient with the possibility of QT interval abnormality was also excluded. Patients in the intervention group received 10 mg (2 ml) of intravenous metoclopramide, and patients in the control group received 2 ml of distilled water.

3.4. Ultrasonographic Assessment

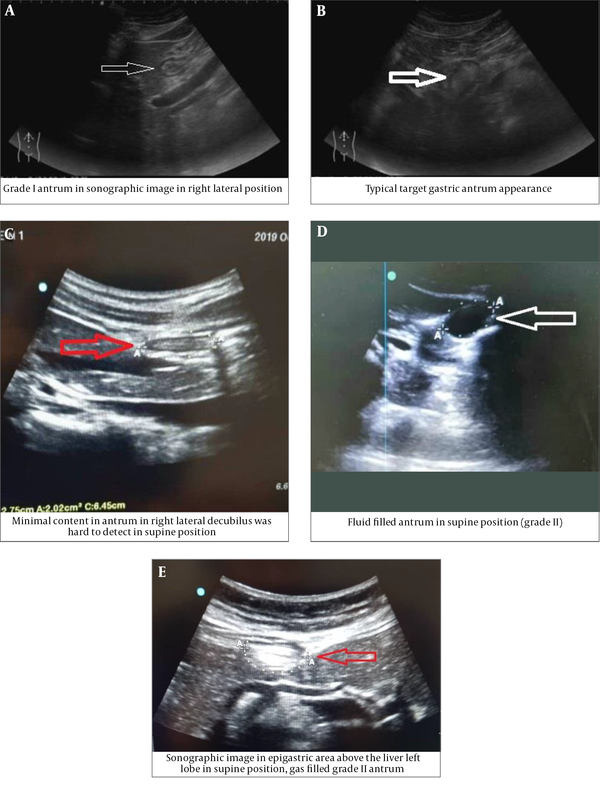

Patients in both groups underwent ultrasonography (machine model: Sonosite edge 2; Probe: rC60xi 2-5 MHz) in supine and right lateral position (RLP) by an expert radiologist (Figure 1A-E). In both positions, the gastric antrum was identified and measured in the sagittal view with its anatomical landmarks. Qualitative examination is used to identify substances in the stomach (solid or liquid) and gastric antral grade (GAG) in the form of grade 0 (absence of fluid), grade 1 (fluid in RLP position only), and grade 2 (fluid in both supine and RLP position). Quantitative evaluation is in the form of an antral cross-sectional area (CSA). The CSA is calculated by measuring the vertical thickness in the longitudinal (d1) and posterior (d2) planes, both in centimeter, from serosa to serosa, and using the formula CSA = 3.14 (d1 × d2) ×0.4. The cut-off value of the antral CSA for the diagnosis of gastric fluid volume > 1.5 ml/kg and/or solid/thick fluid contents was 3.01 cm2 (16).

(A-E): Ultrasonographic Qualitative Examination

The onset of pharmacological action of metoclopramide is 1 to 3 minutes following an intravenous dose and reaches its peak effect in less than 30 minutes. Therefore, these measurements were then taken for the second time 30 minutes after intervention, before starting the surgery.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Variable frequencies are described in percentage, mean with standard deviation (SD), and also median, as appropriate. The qualitative, categorical, variable distribution in two study groups was assessed with Chi-square or Fisher exact test. The mean difference of numerical variables in two study groups was analyzed by independent t-test, and the mean difference of before and after intervention was analyzed by paired sample t-test. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test and graphical approaches for assessing normality assumptions. The gastric antral grade (GAG) and distribution changes after and before intervention in metoclopramide and control groups were assessed with the Mantel-Haenszel test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All of the analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS v-24.

4. Results

The data of 60 patients were analyzed, of which 30 were in the intervention group (metoclopramide) and 30 in the control group (placebo). The patients’ baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The mean age of the patients in intervention and control groups was 40.7 (SD = 17.1) and 45.3 (SD = 19.6), respectively. The mean age, BMI, type of the last consumed food (solid or fluid), NPO time in the intervention, and control groups were not significantly different (P value > 0.05).

The Patient Characteristics, Type of Consumed Food and NPO Time Difference in Intervention and Control Group

| Metoclopramide Group (N = 30) | Placebo Group (N = 30) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 40.7 (17.1) | 45.3 (19.6) | 0.334 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 69.6 (12.8) | 67.9 (13.2) | 0.622 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.07) | 1.7 (0.08) | 0.192 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 23.9 (3.9) | 23.9 (4.1) | 0.928 |

| Consumed food, No. (%) | 1 | ||

| Liquid | 28 (93.3) | 28 (93.3) | |

| Solid | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | |

| NPO Time (hour), mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.4) | 0.562 |

Before intervention, GAG was in grade 2 for the majority of patients (56.7%) in the intervention group and grade 2 in the control group for 36.7% of patients. The highest distribution of patients in the metoclopramide group in the higher GAG before the intervention in comparison with the control group showed a significant difference (P value = 0.001). Also, the mean CSA scores before intervention were significantly higher in metoclopramide than the control group, as much as 2.1 units (P value = 0.004).

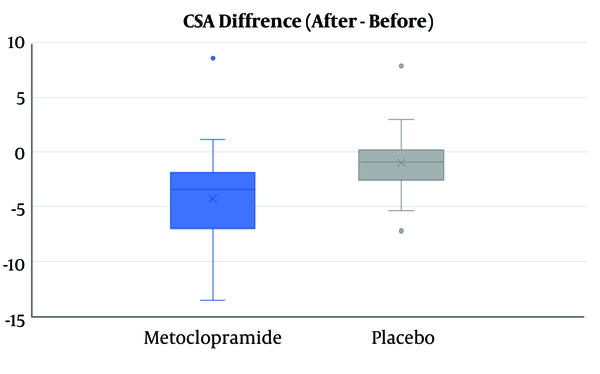

Although GAG and mean CSA score after intervention were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2), the mean difference of decrease in CSA in the metoclopramide group was more than the control group (4.3 vs. 0.99), and this difference was statistically significant (P value = 0.001) (Figure 2).

The Gastric Antral Grade (GAG), CSA Mean Score in Before and After Intervention and CSA Difference in Metoclopramide and Control Group

| Metoclopramide Group (N = 30) | Placebo Group (N = 30) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAG before intervention, No. (%) | 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (36.7) | |

| 1 | 13 (43.3) | 8 (26.7) | |

| 2 | 17 (56.7) | 11 (36.7) | |

| CSA before intervention, mean (SD) | 10.8 (5.2) | 7.1 (4.4) | 0.004 |

| GAG after intervention, No. (%) | 0.382 | ||

| 0 | 9 (31.0) | 8 (26.7) | |

| 1 | 18 (62.1) | 16 (53.3) | |

| 2 | 2 (6.9) | 6 (20.0) | |

| CSAa after intervention, mean (SD) | 6.6 (3.2) | 6.1 (3.2) | 0.573 |

| CSA difference, mean (SD) | -4.3 (4.4) | -0.99 (2.8) | 0.001 |

The box Plot of Distribution of CSA Difference Before-and-After Drug Administration in Intervention and Control Group (values were reported in cm2)

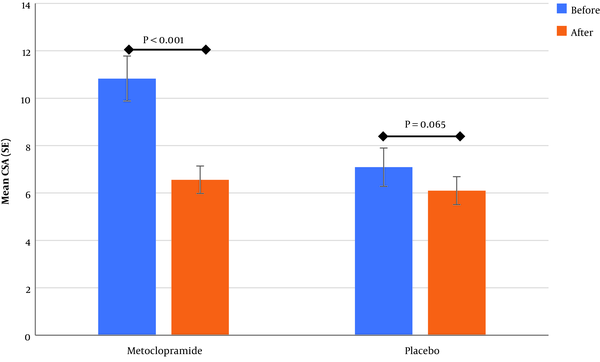

The analysis of study groups showed that the mean of CSA decreased in both the metoclopramide and control groups after the intervention, although the decrease was significant only for the metoclopramide group (Figure 3). The comparison before and after the intervention for GAG showed that change after intervention to lower levels in the metoclopramide group was more than the control group, and was statistically significant in both groups (P value < 0.05). Therefore, of the total patients with grade two in the metoclopramide group, before intervention (N = 16), 25% and 62.5% changed to grade zero and one after the intervention, respectively. These changes in the control group was zero and 45.5%, respectively (Table 3). In addition, in the quantitative comparison, the median GAG after the intervention had changed from two to one in the intervention group and was equal to one in the control group before and after the intervention.

The Gastric Antral Grade (GAG), and Distribution Changes After and Before Intervention in Metoclopramide and Control Group

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | Total | ||

| Metoclopramide, No. (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (100) | |

| 2 | 4 (25.0) | 10 (62.5) | 2 (12.5) | 16 (100) | |

| Total | 9 (31.0) | 18 (62.1) | 2 (6.9) | 29 (100) | |

| Placebo, No. (%) | 0.033 | ||||

| 0 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100) | |

| 1 | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100) | |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 11 (100) | |

| Total | 8 (26.7) | 16 (53.3) | 6 (20.0) | 30 (100) | |

The Mean of CSA in Before-and-After Drug Administration in Intervention and Control Group (values were reported in cm2)

5. Discussion

In the current study, we found that metoclopramide could reduce gastric ultrasonographic indexes, including GAG and CSA, which are correlated with the gastric content volume in patients with incomplete fasting before induction of general anesthesia.

As mentioned, most still recommend proper fasting time before induction of general anesthesia as usual practice (2-4). However, the effectiveness of standard fasting guidelines has been assessed by gastric ultrasonography, and no correlation was found between hours of fasting and residual gastric volume, and despite compliance with fasting guidelines, some patients are still at risk of aspiration (17, 18). Therefore, it seems that interventions may be needed to facilitate gastric emptying before the induction of general anesthesia or anesthesiologists should consider another technique for their patients, particularly in emergency cases. Prokinetic administration is among interventions that have been tried in this regard. Such agents are categorized as dopamine antagonists (i.e., metoclopramide), serotonergic agonists (i.e., cisapride), motilin receptor agonists (i.e., erythromycin), cholinergics (i.e., bethanechol), and other agents. Choosing a proper agent for accelerating gastric empting before induction of general anesthesia is based on many factors such as type of surgery, duration of surgery, possible side effects, potential drug interactions, and underlying disease. Metoclopramide, which has been used in the current study, is a well-known drug in this regard which could lead to extrapyramidal reactions and QT prolongation; so it is highly recommended to take a complete history, perform an electrocardiogram (ECG), review potential drug interactions and electrolyte abnormalities that can increase the QT interval (19).

In a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, findings of previous studies in which the role of promotility agents (including cinitapride, cisapride, domperidone, Ghrelin, itopride, relamorelin, revexepride, and Tzp 101/102) had been assessed by optimal or suboptimal gastric emptying test methods (breath test and scintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound), were reviewed and it was found that these agents significantly accelerate gastric empting. This review, though, included “metoclopramide” as one of its keywords in the search strategy and found seven trials conducted from 1982 to 2015, but there was not any trial in which its effect had been assessed with any of the optimal gastric emptying test methods. In those seven trials, the results had controversies. In two studies, the results were in favor of metoclopramide efficacy on accelerating gastric emptying, and in one study, the results were reported in the opposite direction, and in the other four, the results did not directly address the intended purpose (20).

In a study by Sustic et al., the effect of metoclopramide was compared with placebo on gastric emptying of patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting, albeit in the post-surgical period, was assessed; in which paracetamol had also been administered concurrently in both groups and plasma paracetamol concentration was measured as a proof test. They concluded that a single dose of intravenous metoclopramide effectively improves gastric emptying (21), using bedside sonography as a suboptimal gastric emptying test method. It should be mentioned that although preoperative bedside gastric ultrasound could be useful in terms of gastric volume measurement, it can not provide all the required information such as gastric function and pH of its content. On the other hand, there is also a complex interaction between viscosity, osmolality, calorie load, volume, time with the gastric emptying process that all need to be considered and should be kept in mind when interpreting the results (22, 23).

5.1. Limitations

We did not perform patient randomization, and as it was mentioned in the results part, the two study groups were not homogenous in terms of primary (before intervention) ultrasonographic assessed indexes; and it has made it somewhat difficult to discuss the results. Also, aspiration did not occur in any of the studied patients, so it cannot be claimed that this intervention could change the incidence of this complication. It is highly recommended to study the role of risk factors and underlying disease such as opioid use, chronic kidney disease (CKD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, neuromuscular disease on the one hand, and also viscosity, osmolality, calorie load, volume, time on the other hand in further similar studies. Metoclopramide is inexpensive, is easy to administer, and has a low incidence of major adverse effects in the dosages commonly used in the preoperative setting. It is reasonable to investigate whether it has some useful benefit in reducing gastric volumes prior to surgery, even though it may be difficult to demonstrate a significant effect on clinical outcomes without a very large study. The recent development and use of gastric ultrasound means that a study of its applicability in preoperative patients with sub-optimal fasting is of great interest.

In conclusion, in the current study in which ultrasonographic indexes, including GAG and CSA, were assessed as a suboptimal gastric emptying test method, it was found that metoclopramide could accelerate gastric emptying compared with placebo in patients with incomplete fasting before induction of general anesthesia.

5.2. Main Points

1. It seems that patients with incomplete fasting have a higher risk of aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia during general anesthesia.

2. Measurement of gastric content and volume, using ultrasonographic indexes, including GAG and CSA, could be valuable as a part of perioperative patient assessment.

3. Administration of metoclopramide could accelerate gastric emptying in patients with incomplete fasting before induction of general anesthesia.

References

-

1.

Kluger MT, Culwick MD, Moore MR, Merry AF. Aspiration during anaesthesia in the first 4000 incidents reported to webAIRS. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2019;47(5):442-51. [PubMed ID: 31438719]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057X19854456.

-

2.

Larson F, Nystrom I, Gustafsson S, Engstrom A. Key Factors for Successful General Anesthesia of Obese Adult Patients. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019;34(5):956-64. [PubMed ID: 31151885]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2019.01.009.

-

3.

Larson Jr CP, Jaffe RA. Practical Anesthetic Management: The Art of Anesthesiology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

-

4.

Cook TM. Strategies for the prevention of airway complications - a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(1):93-111. [PubMed ID: 29210033]. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14123.

-

5.

Abdolrazaghnejad A, Banaie M, Safdari M. Ultrasonography in emergency department; a diagnostic tool for better examination and decision-making. Adv J Emerg Med. 2018;2(1).

-

6.

Nasr-Esfahani M, Behravan M, Esmailian M. The Correlation between Ultrasonographic Gastric Antral Area and Vomiting in Patients undergoing Procedural Sedation and Analgesia. Adv J Emerg Med. 2019.

-

7.

Perlas A, Mitsakakis N, Liu L, Cino M, Haldipur N, Davis L, et al. Validation of a mathematical model for ultrasound assessment of gastric volume by gastroscopic examination. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(2):357-63. [PubMed ID: 23302981]. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318274fc19.

-

8.

Mehta S, Saroa R, Palta S, Mehta D. An evaluation of the comparative efficacy of preoperative oral omeprazole, lansoprazole and dexrabeprazole on gastric fluid pH and volume in patients undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Northern Journal of ISA. 2016;1(2):54-7.

-

9.

Bruley des Varannes S, Gharib H, Bicheler V, Bost R, Bonaz B, Stanescu L, et al. Effect of low-dose rabeprazole and omeprazole on gastric acidity: results of a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, three-way crossover study in healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(8):899-907. [PubMed ID: 15479362]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02176.x.

-

10.

Sebrechts T, Perlas A, Abbas S, Van de Putte P. Serial Gastric Ultrasound to Evaluate Gastric Emptying After Prokinetic Therapy With Domperidone and Erythromycin in a Surgical Patient With a Full Stomach: A Case Report. A A Pract. 2018;11(4):106-8. [PubMed ID: 29634526]. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000000755.

-

11.

Kopp VJ, Mayer DC, Shaheen NJ. Intravenous erythromycin promotes gastric emptying prior to emergency anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1997;87(3):703-5. [PubMed ID: 9316982]. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199709000-00037.

-

12.

Adelhoj B, Petring OU, Pedersen NO, Andersen RD, Busch P, Vestergard AS. Metoclopramide given pre-operatively empties the stomach. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1985;29(3):322-5. [PubMed ID: 3993321]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1985.tb02208.x.

-

13.

Howard FA, Sharp DS. Effect of metoclopramide on gastric emptying during labour. Br Med J. 1973;1(5851):446-8. [PubMed ID: 4689832]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC1588429].

-

14.

Liu Y, Dong X, Yang S, Wang A, Wang M. Metoclopramide for preventing nosocomial pneumonia in patients fed via nasogastric tubes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016.

-

15.

Hakak S, McCaul CL, Crowley L. Ultrasonographic evaluation of gastric contents in term pregnant women fasted for six hours. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2018;34:15-20. [PubMed ID: 29519668]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.01.004.

-

16.

Bouvet L, Chassard D. Ultrasound assessment of gastric contents in emergency patients examined in the full supine position: an appropriate composite ultrasound grading scale can finally be proposed. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020;34(5):865-8. [PubMed ID: 31853813]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-019-00452-3.

-

17.

Sharma S, Deo AS, Raman P. Effectiveness of standard fasting guidelines as assessed by gastric ultrasound examination: A clinical audit. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62(10):747-52. [PubMed ID: 30443056]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC6190433]. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_54_18.

-

18.

Ohashi Y, Walker JC, Zhang F, Prindiville FE, Hanrahan JP, Mendelson R, et al. Preoperative gastric residual volumes in fasted patients measured by bedside ultrasound: a prospective observational study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;46(6):608-13. [PubMed ID: 30447671]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057X1804600612.

-

19.

Gudsoorkar V, Quigley EMM. Choosing a Prokinetic for Your Patient Beyond Metoclopramide. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(1):5-8. [PubMed ID: 31714358]. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000463.

-

20.

Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Chedid V, Mandawat A, Erwin PJ, Murad MH. Effects of Promotility Agents on Gastric Emptying and Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1650-60. [PubMed ID: 30711628]. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.249.

-

21.

Sustić A, Zelić M, Protić A, Zupan Z, Simić O, Desa K. Metoclopramide improves gastric but not gallbladder emptying in cardiac surgery patients with early intragastric enteral feeding: randomized controlled trial. Croatian Med J. 2005;46(2):239-44.

-

22.

Benhamou D. Ultrasound assessment of gastric contents in the perioperative period: why is this not part of our daily practice? Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):545-8. [PubMed ID: 25354945]. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu369.

-

23.

Okabe T, Terashima H, Sakamoto A. Determinants of liquid gastric emptying: comparisons between milk and isocalorically adjusted clear fluids. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(1):77-82. [PubMed ID: 25260696]. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu338.